Previously on Midlife Crisis Crossover: Oscar Quest ’25 continues! Once again we see how many among the latest wave of Academy Award nominees I can catch before the big ABC ceremony, regardless of whether or not I’ve previously connected with the subject matter in the slightest, and whether or not I’ll sound like a philistine to said subject’s biggest fans who outnumber me 500 million to 1. It wouldn’t be my first time speaking as an ignoramus who’s willing to learn.

Over the years James Mangold has directed films of all sizes and accumulated enough goodwill among studios and audiences alike that he’s now alternating between them — not exactly the vaunted “one for them, one for me” model of project selection, considering the last time he spent under $20 million on a film was 1997’s Cop Land. A steady career of dramas (and one fantasy-lite rom-com, the underrated Kate & Leopold) segued into blockbuster franchising with The Wolverine and Logan (still in my superhero-film Top 3), returned to true-story territory with Ford v. Ferrari, then was handed the golden keys to the Indiana Jones series and…uh, lost a lot of Disney’s money, but at least he helped the old man live down the one with Mutt and the aliens in it.

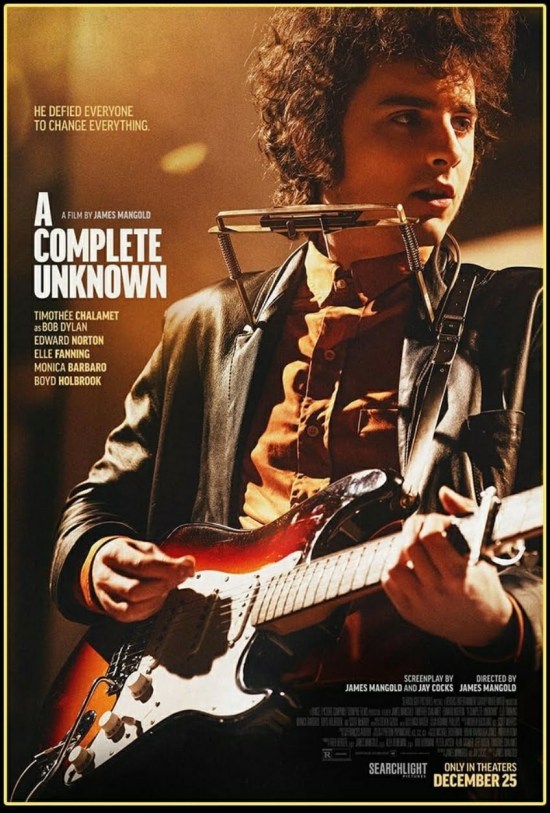

Mangold manages to do more with a little less in A Complete Unknown, technically another biopic in the manner of his Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line, though it only covers a five-year period — the early years of Bob Dylan, which seem enough to convey his impact on the world of folk music and stopping short of…well, the last five decades of his career that fell within my lifetime. Hence why I procrastinated seeing this ever since its Christmas Day release until after it was a confirmed Oscar nominee rather than a presumptive one: folk music is generally not my thing.

Personally, I blame lack of exposure. My mom amassed stacks of 45s in her time, but I never noticed Dylan in them. Local radio never played his music unless you count the Traveling Wilburys’ first single, which I’m pretty sure doesn’t count. I’ve seen a few films set in the folk world that were enjoyable despite my lacking frames of reference and probably missing hundreds of nuances (e.g., Inside Llewyn Davis, Bob Roberts). A few folkies found their way into my collection — oldies like Simon and Garfunkel, as well as heavily influenced latecomers like John Wesley Harding. And of course my tapes and CDs have countless Dylan covers scattered throughout. (Hendrix! The Byrds! Ramones! Mike Ness! Red Hot Chili Peppers! My Chemical Romance! Matthew Sweet and Susanna Hoffs! Doubtlessly more!)

But most of what my brain labeled “folk music” was probably unduly influenced by all those TV commercials for Time-Life flower-child compilations, which mashed it all together into one big acoustic humdrum lump. Funny thing about ignorance, though: it isn’t fatal and it is curable through exposure to the subject in question. Repeated exposure is best, sure, but…y’know, baby steps. Ten minutes into the film, my hesitation was gone and I wanted to hear more. Progress!

The most important factor for overcoming my reluctance to engage with the material is Timothée Chalamet’s exemplary performance as the man, the myth, the legend himself. (Or maybe he sucks and got Dylan all wrong? I wouldn’t know!) In 1960 Dylan the youthful Midwest nobody arrives in NYC with instruments, duffel bag, and a cache of precocious talent. As he connects with the old men of the folk world and demonstrates his lyrical chops and technique, Chalamet balances a stark contrast between that lucidly enunciating stage persona and the intensely introverted mumbler away from the mic — the latter being the easy basis of the last five decades’ Dylan parodies from “Weird Al” to SNL and beyond.

Mangold plays up the contrasts between Dylan and the more established artists who witnessed his arrival. By this time his idol Woody Guthrie (Scott McNairy from Argo and Dawn of Justice) is permanently hospitalized with Huntington’s disease and can barely communicate, but he can listen and, in his own way, give feedback. Pete Seeger checks in on Guthrie regularly in between other projects, such as a music showcase on a local PBS station and overseeing the annual Newport Folk Festival. As played by Academy Award Nominee Edward Norton, Seeger has a high threshold for absorbing stress and bad vibes, and comes off as the community’s step-parental Mister Rogers. He’s a bona fide folk authority who hears the right kind of magic coming out of Dylan’s guitar, harmonica, and unique voice. Well, at least at first.

Impressing Seeger leads to Dylan’s first open-mic number, taking the platform right after the Joan Baez, played by Monica Barbaro (Top Gun: Maverick, Stumptown). Only a year older than Dylan, Baez is a rising star herself, but her incredulous approval of this rookie’s debut carries weight, especially with a particular guy in the audience — established folk manager Albert Grossman (Dan Fogler from Fanboys and the Fantastic Beasts series). A few phone calls later, Dylan is on his way to a genuine musical career! And, for a while, a standard biopic life template!

Chalamet’s Dylan naturally endures myriad drawbacks on his way to success. Old-fogey producers insist he record only covers and won’t listen to his originals. His first big-city girlfriend Sophie (ex-child star Elle Fanning) puts up with his every foible until he reaches a certain level of insufferability and cheats on her with Baez. Before long he’s racking up hit singles like “Blowin’ in the Wind”, acquiring the superpower to make young ladies scream at him like he’s all four Beatles combined into a single Voltron of folk music, and mocking other folkies he now perceives as his lessers. (Peter, Paul and Mary suffer burns, among a couple others.) Fame becomes a stone cold drag, and he still spars in the studio with everyone else’s ideas about what he “should” do. He nearly implodes as his introversion intensifies, coming off Jekyll-and-Hyde to anyone who doesn’t get him, which is nearly all the other characters after a while, including his sainted peer Baez. They nearly come to blows when Dylan unconditionally asserts he will LOSE IT if he has to play “Blowin’ in the Wind” ONE MORE FRICKIN’ TIME.

(I was even less familiar with Baez going into this. Barbaro’s performance as the feminist icon, onstage and off-, shifts from collegial admiration to Something More to furious betrayal and cements the film’s perspective that all this is not trying to canonize Dylan. He’s so deeply irritating in this middle phase. Also: having heard possibly no Baez in my entire life until Barbaro’s recreations here, now I get where Tori Amos cribbed her sound.)

Mangold centers the musical numbers without turning them into music videos, accentuating the performances first while the musicality follows. For the sake of keeping the runtime under six hours, nearly every song is reduced to one chorus and one verse — a weird artifice to get used to, but more than enough of a sampler for each track, which of course we viewers are free to go look up later. The theatrical immersion worked wonders for me, surrounded in a nearly empty theater by a sound system dozens of decibels better than my home setup (which is always necessarily muted because our house is small, my family doesn’t quite share my sound-level preferences, and someone else is always home). Hearing the Masters of Folk cranked up and not filtered through earbuds was definitely the best way to experience a lot of these songs for my first time.

Admittedly I may have laughed more than a few times as Unknown sped on toward its final, most controversial confrontation: the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, to which Dylan was invited but then nearly uninvited because he threatened to perform with…electric guitars! Gasp! Choke! Heresy! Judas! (Someone actually yelled this at the time, which Mangold keeps in!) Diehard folkies who consider “folk rock” an oxymoron apparently presaged today’s internet cliques who threaten grievous bodily harm if the caretakers of their lovingly worshiped idols dare make any “wrong” changes. Nearly five decades later it might seem amusing to me, but the Newport ’65 meltdown over plugged-in power chords was a real thing they never taught us in school. It’s the fitting climax of Mangold’s entire five-year arc about Dylan’s struggle for creative control — a vivid theme that was also central to Ford v. Ferrari, but with engines instead of music. Both make us move, but the real trick is in how their makers want us to move.

Despite its familiar storytelling pattern, A Complete Unknown can claim a certain uniqueness to it beyond Dylan’s music: how many biopics do you know that end with the subject getting violently chased off a stage and claiming it as a personal triumph? And how many biopics leave me wanting to get more into the subject beyond just their Wikipedia entry?

(Not even kidding. The last several paragraphs were cranked out while listening to Highway 61 Revisited in its entirety for my first time. See, now I can appreciate it.)

…

Meanwhile in the customary MCC film breakdowns:

Hey, look, it’s that one actor!: Very loud mention must be made of Boyd Holbrook (who worked with Mangold in Logan and Indy 5), an apt choice to play the boisterous legend Johnny Cash, another of Dylan’s biggest influences who crosses his path at the right time. Cash’s family isn’t around, but some of his favorite substances sure are.

Blues musician Big Bill Morganfield (son of Muddy Waters!) is a blues musician who puts up with Dylan when he arrives unexpectedly during the taping of Seeger’s show. Eriko Hatsune (2012’s Emperor) is Seeger’s wife Toshi. Charlie Tahan (Gotham’s Scarecrow) is keyboardist Al Kooper, original player of the familiar organ hook on “Like a Rolling Stone”.

P.J. Byrne, no stranger to playing annoying guys in charge (Babylon, The Boys), is folk manager Harold Leventhal. Norbert Leo Butz (who got to chase Holbrook around in Justified: City Primeval) is Alan Lomax, a music preservationist. Michael Chernus (Severance, Spider-Man: Homecoming) is actor Theodore Bikel, co-founder of the Newport Folk Festival. SNL’s James Austin Johnson (their current Trump guy) pops by as an emcee.

How about those end credits? No, there’s no scene after the A Complete Unknown end credits, though I was briefly interrupted as they rolled. As two older ladies in the row ahead of me began to leave, the younger said something I didn’t quite hear, then proudly told me her nephew was actually in the film — a single scene involving a man in Sophie’s apartment, of whom we only see his legs and hear him utter a sleepy question. Kudos to you, nephew.

After they left, the credits confirm Chalamet, Barbero, Norton, and Holbrook sang all their own songs. And by the very end, now alone in the theater, I found myself singing along with the final song, Chalamet’s rendition of “Mr. Tambourine Man”. I understood that reference!

Discover more from Midlife Crisis Crossover!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.