Previously on Midlife Crisis Crossover: Oscar Quest ’25 continues! Once again we see how many among the latest wave of Academy Award nominees I can catch before the big ABC ceremony. The rules are simple and the points don’t matter to anyone but me.

Critics had already been raving about The Brutalist weeks before a big night at the Golden Globes gave it some light mainstream recognition. Based on the buzz, I saw it two days before its Oscar nominations were announced so I could cross it off my checklist in advance. AMPAS voters traditionally love sweeping epics at the intersection of personal ambition and world history, regardless of runtime or controversies. Director/co-writer Brady Corbet (Vox Lux) and co-writer Mona Fastvold (Apple’s The Crowded Room) figured the time was right for a resonant, fictional, occasionally ugly tale of underestimated immigrants, family rent asunder, talent discovery, teamwork, overreach, exploitation, and how the symbiosis between artist and patron can drift from reign to rot.

Two decades plus after winning Best Actor for Roman Polanski’s The Pianist, Adrien Brody returns to World War II as another starving artist with a different homeland. Relocating his accent from Poland to Hungary, Brody is László Tóth, an accomplished Bauhaus architect who survives the Holocaust and makes the long journey to America alongside millions of other displaced Europeans who brought their skill sets but didn’t necessarily find the fast track from the immigration station to career revival. At first he finds safe harbor with his cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivola, bouncing back from Kraven the Hunter) and handcrafts modernist furniture that’ll look cool in some Sterling Cooper exec’s spare apartment. When that arrangement sours, László hits the pavement and dwells for a time down in the American underbelly that never makes it into the travel brochures we airdrop overseas.

After a stretch of hard labors and misery, a confluence of some talent and much fantastic luck pays off, not unlike the average famous person. László’s penchant for unorthodox interior design comes to the attention of a powerful man in a position to change his fortune, or at least throw part of a fortune at him. Guy Pearce (L.A. Confidential! Memento! Iron Man 3! more!) is Harrison Van Buren, an eccentric millionaire (which used to be rich enough for our tycoons, back in the day) who, after an awkward meet-brute, does some research — without the internet, even! — and realizes the significance of the peasant in his presence, one who’s just built him a personal library that’s the envy of all his snobby peers. Van Buren is the sort of stoic man’s-man they made back in the day, fastidious and precise and dismissive of anyone intimidated by his steel jaw unless he can use them. László might just be the tool he’s looking for.

Van Buren wants a revolutionary architect to realize the headiest vision of his entire life: a massive community center out in the grassy hills of Doylestown (a few dozen miles north of Philly) that he wants to be an auditorium, a gym, a library and a chapel. If you’ve ever seen The Simpsons‘ season-2 episode “Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?”, imagine The Homer but instead of an amalgamated jalopy designed by an unchecked idiot, it’ll be an intimidating Swiss-knife tower that screams “folly” as can only be screamed by the works of an egotist with far too much money. László is enticed by the possibility of leaving poorness behind, but soon he’s caught the contagious gleam in Van Buren’s eye and imagining how he can totally pull it off. All he needs is total creative control, unlimited resources, the people of Doylestown to stop looking at him weird, and God to refrain from laughing at his plans for a while. What’s the worst that could happen?

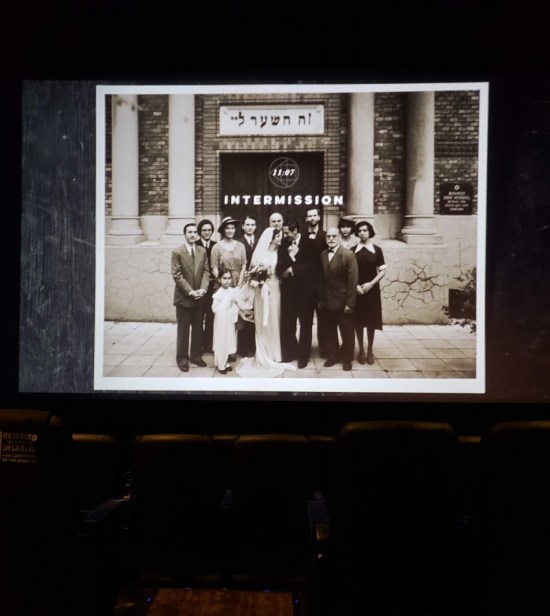

That’s only half the movie. Over 3½ hours long, The Brutalist is the first film I’ve seen in theaters with an intermission since Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet back in 1996. The 15-minute break around the 1:45 mark was a great opportunity to hit the bathroom, empty out phone notifications, and chat with the other audience members.

Next after the break: László’s wife arrives! Felicity Jones (Rogue One, The Theory of Everything) enters the picture as former journalist Erzsébet Tóth, seen in a brief prologue and existing mostly as a pen-pal for years, finally arriving in the flesh in the second act as a reward for László from Van Buren and God (in that order if you ask Van Buren). She’s brought along their last surviving relative, their niece Zsófia (Tomorrowland‘s Raffey Cassidy), and a major life change that she left out of her letters because she didn’t want to be any trouble.

In a more pedestrian film Erzsébet would be either a Concerned Wife prop tucked in a closet or a hectoring meddler whose petty shrieks single-handedly disrupt the project and bring their would-be skyscraper collapsing to the ground. On the contrary: László’s stresses and sins have multiplied during their overlong separation, and her arrival brings on a much-needed reckoning. Awkward and tentative at first, Brody and Jones ease their way back toward a marital synchronicity with maturity and sensitivity whenever László isn’t ruining everything. The worse things get among the menfolk, the more Jones steps up and the more room Corbet wisely makes for her. She brings the one element that was drowning in the testosterone pool: the film’s conscience.

Meanwhile back at the construction site, everything’s falling apart. Van Buren’s dream center graduates from a team project to a mutual obsession. László falls int the temperamental-artist nonfictional-biopic trap and of course has tantrums about no one respecting his ideas or following his instructions or being good enough to carry it all out. As the years drag on and the overruns pile up, Van Buren has to concede he isn’t Howard Hughes and his money bin does have limits. The men keep making plans and God won’t stop laughing at them.

In between workshop arguments down amongst the girders, Corbet keeps his movements sweeping and the emotions hyped-up here at the intersection of labor and management, of feasibility and safety, of teamwork and ego as the man with the pencils and the man with the purse strings race toward the edge of sanity and see who falls off the edge first. Perversely, very few of those confrontations actually happen in awesome-looking buildings. Mostly those are seen in photos, blueprints and coffee table books. The film’s most beautiful sequence leaves Doylestown behind as the guys visit a marble quarry in Carrara, Italy — a glorious wonder unto itself, especially if you’re like me and never wondered what marble looks like in its natural state before humankind extracts it and turns it into monuments to themselves, and into countertops for tiny children to befoul by making peanut butter sandwiches on it.

Lest we get too carried away by all the marble-shopping fit for an HGTV special, the Carrara trip ends with a quiet, shadowed, unmistakable rape scene. Arguably it’s one among the serial moments of brutality stretched to fit the architectural motif (putting the “brutal” in Brutalism?) and Corbet’s dissertation on the dysfunctional side of the American dream, which some viewers might defend at length on scholarly character-arc grounds or whatever. (“It’s a metaphor for what employers do to employees!” Sorry if that’s been your extremely limited-in-scope occupational experience.) Others among us now have this planetary-sized asterisk looming above the overall creation, trying to appreciate the rest of the accomplishment with a footnoted contortion to the effect of “Setting aside one or two hideous moments I never want to sit through again, The Brutalist is a towering cinematic achievement! I sure hope they only quote that last part on the poster!”

Or maybe that’s just me, once again the prude in the minority. Even without a single review bringing up that scene, the film had its share of controversies even before it qualified for Oscar Quest inclusion. Apparently László’s life and building-ography mix and match from real-life architects of considerable renown, using details specific enough to spur a backlash over What The Brutalist Gets Wrong About Architecture. In even larger fonts are the headlines about Corbet and his crew using A.I. tech to fix the Hungarian dialogue’s accents (like an extremely specific Auto-Tune) and add defects to some pieces of art in the epilogue so they look intentionally dated and awful. I like to think a human could’ve managed that much, but somehow spending ten million on everything else up to that point didn’t leave any more wiggle room for luring in a DeviantArt user with some high school drafting classes under their belt.

At the end of a long evening, The Brutalist experience leaves us with one last “twist” punchline that’s either a baroque redemption of utmost evil or a tribute act borne of chutzpah and madness, depending on how much you favor an artist’s intent over their results. It’s like an actual Brutalist building that favors stark right angles, weird gaps, death to curves, and the miserable end of the rainbow — not about being pretty or contributing flourishes to a community’s skyline — but some of its interior decorations might spark a sort of joy.

…

Meanwhile in the customary MCC film breakdowns:

Hey, look, it’s that one actor!: Joe Alwyn (The Favourite) is Van Buren’s adult son, who’s even snobbier and shortsighted than Dad, which he plays entirely in a Jesse Plemons mode. Emma Laird (A Haunting in Venice, Mayor of Kingstown) is cousin Attila’s wife, one of the reasons he converted to Catholicism, which makes both of them all the more skittish around László. Isaach de Bankolé (Night on Earth, Calvary) is a pal of László’s during his homeless phase, who then becomes his trusty sidekick in matters of building and drugging.

Jonathan Hyde (the original Jumanji, Stephen Sommers’ The Mummy) is a middle-manager who represents for the Doylestown villagers and chafes at taking orders from László until he gets used to him and maybe, just maybe, learns a little lesson about tolerating outsiders.

How about those end credits? No, there’s no scene after The Brutalist end credits, but apropos of the concept, the credits roll at a 40-degree angle from the lower-left corner to the upper-right corner of the screen, from start to finish.

And for anyone who thinks Corbet tried to bury the A.I. usage in the fine print, the credit for the accent-fixing device called Respeecher is hard to miss — their logo is as huge as one of László’s projects.

Discover more from Midlife Crisis Crossover!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.