Previously on Midlife Crisis Crossover:

Every year since 1999 Anne and I have taken one road trip to a different part of the United States and seen attractions, wonders, and events we didn’t have back home. From 1999 to 2003 we did so as best friends; from 2004 to the present, as husband and wife. After years of contenting ourselves with everyday life in Indianapolis and any nearby places that also had comics and toy shops, we overcame some of our self-imposed limitations and resolved as a team to leave the comforts of home for annual chances to see creative, exciting, breathtaking, outlandish, historical, and/or bewildering new sights in states beyond our own. We’re the Goldens. This is who we are and what we do.

For 2023 it was time at last to venture to the Carolinas, the only southern states we hadn’t yet visited, with a focus on the city of Charleston, South Carolina. Considering how many battlefields we’d toured over the preceding years, the home of Fort Sumter was an inevitable addition to our experiential collection…

…and here we were, one half-hour ferry ride later, at the star attraction atop our to-do list — the very place where the Civil War began, in the southeastern waters of Charleston Harbor in full view of the Atlantic Ocean. The Army Corps of Engineers began construction of the island in 1829, using 50,000+ tons of granite to create a new base atop a stable sandbar — a project conceived in the wake of the War of 1812, when British invaders unhelpfully exploited our naval vulnerabilities. Little did the ACE know future attacks would be coming from inside the country.

Not Fort Sumter, but Castle Pinckney on nearby Shute’s Folly, owned by the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Public tours aren’t offered, but the flag is swapped out from time to time.

The official welcome sign down by the breakwater, which was moved farther out from the fort walls in 2019.

(As of 2023 its historical parade ground was just four feet above sea level. Flooding becomes an issue with any confluence of high tides and heavy rainfalls. Fortunately this was a sunny day in the immediate vicinity; storm clouds to the southeast kept their distance during our visit and for the rest of the day.)

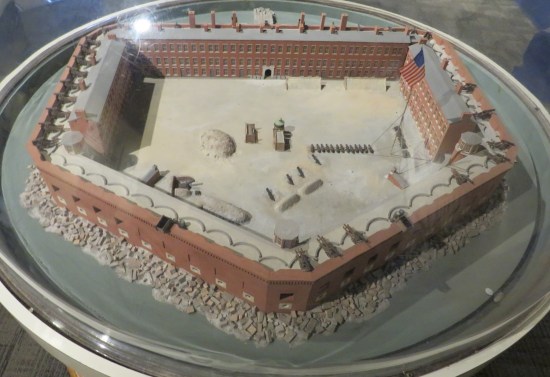

A diorama of Fort Sumter’s full design, had it ever been finished and left unharmed as planned, including barracks and hospital that do not exist today.

(The men’s room was out of order at the time of our visit. The gift shop posted and strictly enforced a max capacity of 15 people — not necessarily because of the recent pandemic, though, as it was also awfully tiny. A much more spacious shop awaited us back on the mainland.)

Most of the pentagonal fort’s square footage is just grass, with all the special features along the walls.

The fort was named in honor of Brigadier General Thomas Sumter, who commanded the South Carolina militia during the Revolutionary War. As is taught in your finer American schools, the Civil War officially commenced when the first shots were fired at the First Battle of Fort Sumter in the wee hours of April 12, 1861. The takeover came three weeks after the infamous “cornerstone speech” given by Alexander Stephens, Vice President of the Confederate States of America, who outlined the CSA’s various grievances and other differences of opinions with the Union, in which he referred to slavery at least eleven times.

The rangers in charge of Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie National Historical Park do not pretend otherwise. Upon our arrival they conducted the daily flag-raising program in which volunteering guests can assist in hoisting the 33-star flag up the pole to replace the losing side’s own. (They carefully noted this was a “program” and not a “ceremony”. Legal flag-care reasons, one presumes.) Their accompanying speech, though enlivened by the ranger’s own lighthearted remarks, unambiguously hammered on the blatant slavery aspect of South Carolina’s intentions.

After the program we were allowed an hour to wander the grounds and see what we could see before the ferry would take off. Sumter marks our fourth visit to an American fort (I think?) after previous road-trip stops at Fort Niagara, Fort McHenry, and Fort Ticonderoga. It’s the smallest of the four, yet arguably the most significant, except maybe to Francis Scott Key groupies.

Features inside the casemates (read: alcoves for cannons) included eleven 100-pounder rifled Parrott cannons that were installed after the Civil War.

One of the Parrott cannons. Note all the embrasures (read: holes in the wall for cannons to shoot through) were all sealed up, so we couldn’t look through them and pretend to target stuff.

Among the few original pieces is the inland-facing Gorge Wall –what’s left, anyway, after so much early shelling before it was fortified with sandbags and cotton bales.

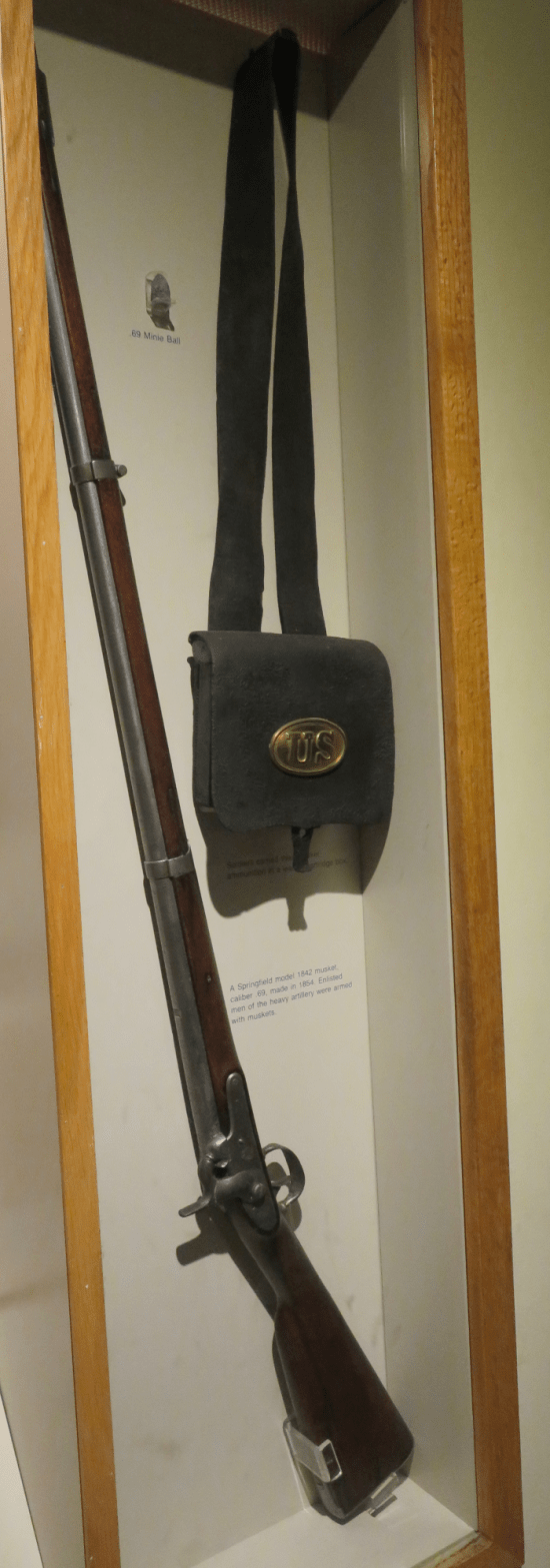

Artifacts and relics were exhibited inside the main structure and in the museum proper, back at the ferry dock.

Model of the USS Keokuk, an experimental Union warship sunk by the Confederates off nearby Morris Island on April 8, 1863.

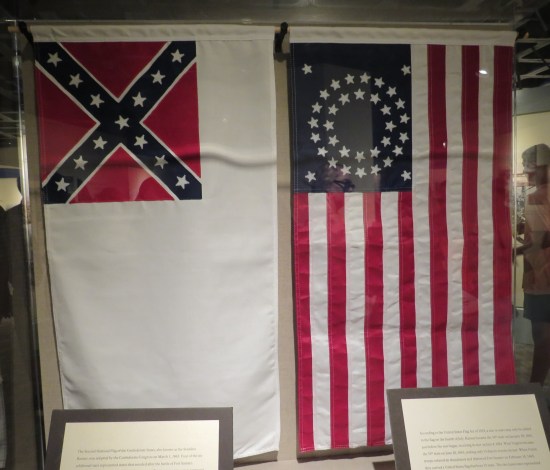

Vintage flags on hand included another Stainless Banner (a.k.a. the Second National Flag of the Confederacy, as we saw earlier on arrival) and the 35-star American flag as of February 18, 1865.

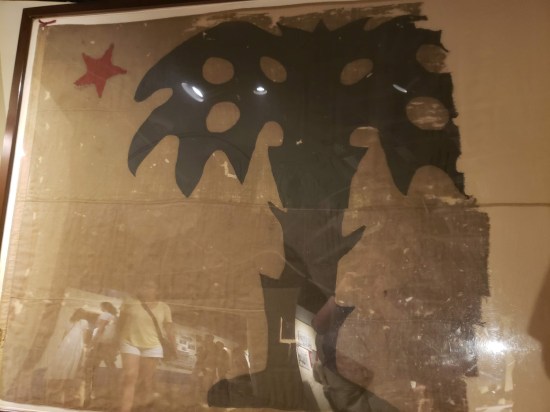

Remnants of the Palmetto Guard Flag, the first flag raised when the Confederates took the fort. The better-known Star and Bars came later that same day.

(As captains of the cotton industry, the South thought they wielded more sway over the federal government until the anti-slavery movement and subsequent laws necessarily upended their antiquated inhumanity. In 1860 America’s cotton earnings were $191,800.00, a good 57% of our total export revenue. Prices further escalated during the war due to scarcity — as of 1863 a 500-pound cotton bale could go for $953.00, which converts to over $24,000.00 in today’s bucks…dependent on the perpetuation of slavery for production. Somehow, hundreds of thousands of casualties later, they eventually learned to do without.)

To learn more about the Civil War, check out your local library or museum gift shop for such books as Jack the Cat That Went to War.

(No, I didn’t buy it, but some online reviewers who read it when they were kids hold it in regard. Apparently it’s the story of a cat who Forrest Gumps his way through life during the Confederate occupation of Fort Sumter and doesn’t judge his slave-owning owners. Readers reportedly do not have to endure scenes of Jack watching nightly slave-whippings with feline disdain while pondering in Garfield-esque thought bubbles, “Wow, sure glad I’m an adorable cat and not a Black person granted pretty much the same rights ’round these parts!” Rumors of a Jack the Cat/Solomon Northup crossover remain as yet unconfirmed by Bleeding Cool.)

To be continued!

* * * * *

[Link enclosed here to handy checklist for other chapters and for our complete road trip history to date. Follow us on Facebook or via email sign-up for new-entry alerts, or over on BlueSky if you want to track my faint signs of life between entries. Thanks for reading!]

Discover more from Midlife Crisis Crossover!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Such a cool visit! Loved the flag-raising part and the way you mix history with personal touches. Can’t wait to read what’s next!

LikeLike

Thanks! More coming soon!

LikeLike