Previously on Midlife Crisis Crossover: class warfare rules in the hands of South Korea’s Bong Joon Ho, from the improbable post-apocalyptic supertrain metaphor of Snowpiercer to the widely celebrated Parasite, Winner of Four Academy Awards Including Best Picture™. Whether it’s the filthy-rich versus the dirt-poor, the genteel-affluent versus the barely-getting-by, or the dirt-poor versus the dirtless-homeless-everythingless, satirical skewerings of the eternal tug-of-war between the have-it-alls and have-nots over their variances in have-measures are very much his favorite field of cinematic dissection.

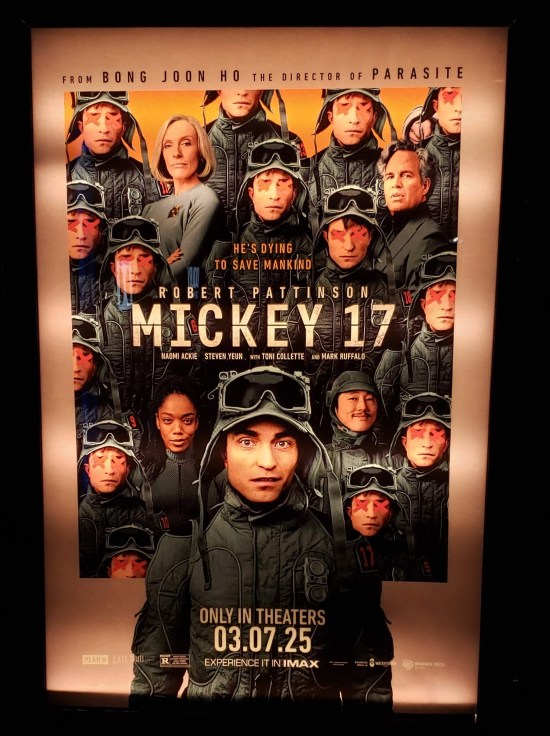

As we waited patiently through the nearly six-year gestation of his post-Oscar follow-up Mickey 17 (the pandemic’s at fault for some of the hold-up), fans rightly expected his priciest foray into the American big-budget mainstream (with a budget twice that of his Netflix Original Okja) would play to his hot-topical interests, and that his knack for outlandish approaches would suit the material. He enjoyed access to better resources, bigger-name actors, and apparently more negotiable schedules for getting it all accomplished. Bong is in his element for much of the film’s first half, up until a midpoint onset of commentary mission-creep pivots everything off the opening premise and lurches toward another course, broader and much tireder.

In a typical sci-fi future where humanity has ruined Earth and seeks someplace else in the universe to relocate and ruin (which describes 85% of the multiverse’s branches), former teen heartthrob Robert Pattinson is neither an astronaut nor an authority figure: he’s a hapless dimwit named Mickey who needs a job and/or sanctuary from a loan shark he stiffed. His past is left vague, probably in case any sequels need flashback fodder — maybe he was a gas station clerk or a YouTuber with six followers, no idea. His rudimentary getaway plan is a crewman gig on a one-way, 4½-year spaceflight to another planet where humanity might begin anew — at least for those followers who could afford the trip and stomach its leaders. Mickey fails to read the fine print, or even the print: he’s the expedition’s sole guinea pig for a series of fatal experiments. Each time he dies, a super advanced 3-D printer cranks out a clone of him, using the ship’s human waste storage compartment for raw materials. He’s reborn with all memories intact and trudges on to his next experiment and his next death. It’s a living!

The entire project is led by evil idiot politician Kenneth Marshall, played by Mark Ruffalo practically as a riff on his over-the-top Poor Things perv, but with a fixation on Space Manifest Destiny instead of sex. He gives an entire speech about the genesis of the disposable-clone tech and the questions it raises about human souls and playing God and whatnot, but extolling its virtues to his audience: “How can we use this abomination for our economic benefit?” Accompanying him as his wife Ylfa is Toni Collette, practically reprising her over-the-top Knives Out influencer but with a fixation on food instead of skin care or money. “Sauce is the true test of civilization!” she proclaims like a Space Instagram foodie. Together they’re spoiled-vapid one-percenter caricatures we’re meant to boo, but they’re unfunny, unserious, and shallowly cloned from other films.

Bong’s take on cloning fits well into his thematic Big Picture: why pay for lots of crewmen when you can just hire the one guy and make copies? It’s like piracy at its most pragmatically callous, yet ironclad contractual like so many factory assembly lines. For some reason they only make one Mickey at a time, and only after the previous one has died. Entire crowds of Mickeys aren’t running around servicing the ship like extra-tall Oompa-Loompas, despite what the movie’s poster implies. Very little creative use is made of the tech, perhaps intentionally stupider than cloning functions in other works. The notion of clones as cheaply recycled, pre-trained labor on demand is the polar opposite of Apple+’s Foundation, where cloning is a form of immortality used only by the intergalactic emperor so he can rule literally forever. Rather, Mickey is all of the guys on the Titanic‘s lower decks. But at least they were meant to survive the voyage.

Mickey’s routine gets complicated when his seventeenth iteration almost dies, prompting the Mickey 18 print job. But as we know, “mostly dead” means “slightly alive”, and soon Mickeys 17 and 18 are living and breathing simultaneously. Just as some Mickey clones exhibited slight deviations from their predecessors, Mickey 18 is fractionally smarter and definitely meaner than our man 17. Pattinson gives his all to both parts, each distinctively realized from the other — the amiable dope cool with coexistence versus the cynical jerk who views his big “brother” as a nuisance who should be dead. Sadly he never gets the chance to play more than two Mickeys at once, again unlike other tales in the cloning mini-subgenre — e.g., the flock of Michael Keatons in Multiplicity, a flawed but fun farce that served up its lead in more varieties. Nevertheless, Pattinson doubly commits to the parts and the inherent existential dilemma of which Mickey copy should be treated as the “real” Mickey. Only occasionally was I bored enough to play “spot the body double in the Mickeys’ shared shot” through no fault of his.

Then something even odder happens: the ship completes the journey and lands on Niflheim, an arctic planet like Hoth or Rura Penthe (which will be more inhabitable than Earth-That-Was’ presumable climate-changed wreckage…uhhhh, somehow magically?), whereupon that whole “cloning” thing in all the trailers and the marketing materials and the main character’s name gets sidelined — y’know, that whole metaphor about disposable cogs in the sociopolitical machinery? — as Bong decides to find a new target for the Marshalls to oppress. In an unsurprising discovery, life already exists on Niflheim, but in the form of seemingly nonverbal sandworm pillbugs that vary in size from plush-merch to sub-kaiju. Kenneth is of course exactly the sort of failed politician to declare open season on them and take the land by force. Our Heroes and possibly a couple other folks farther down the crew complement might have other ideas about how to approach the creatures. This being sci-fi, of course the first question is: what if they’re smarter than we think?

Occasionally the upped VFX budget adds light flair to the claustrophobic spaceship interiors, but the Final Boss Battle on a frozen battlefield is a haze of muddled snowfall and chaos even on an upcharged Dolby Cinema screen, with heavy space vehicles and multi-legged aliens charging at each other and vying for space supremacy while the humans grapple as they’re prone to in third acts. The rest of the cast captures spotlights wherever they can, most noticeably Naomi Ackie (Master of None, Blink Twice) as 17’s Proactive Concerned Girlfriend who works in security, gets one of the cooler action moments near the end, and has to hold the narrative together with her bare hands whenever the Mickeys get too preoccupied with each other’s foibles. Bong doesn’t spend too much time asking which one she’ll take to space prom.

But mostly he’s just brainstorming Ways Rich People Are Awful and seeing how many he can check off on screen before the sweet blockbuster funding runs out. The potential exploitation or extinction of Niflheim’s everyday wildlife aren’t new ground he’s covering — cf. the lukewarm-topical parable of advanced-animal abuse in Okja, or the fleeting wilderness glimpses in Snowpiercer. If they do have true consciousness and communications can be established via universal translator or rigorous Arrival-esque linguistic experimentation, then it’s all just another case of botched first-contact blues — an expensive remake of the Trek episode “The Devil in the Dark”, but this time the Horta are fuzzier and have more on their minds than “NO KILL I”.

We’re back to old-fashioned “imperialism = bad” life lessons, not so much a heartfelt parallel of, say, atrocities against Native Americans. It’s more a lockstep entry in the long line of cautionary tales about put-upon nonhuman lifeforms subject to human-un-kind’s use, abuse, or amusement — King Kong, Dumbo, Free Willy, Pete’s Dragon, the Jurassic trilogies, etc., ad infinitum. Mickey 17 looked pretty cool from a distance and feels fresh at first within its hermetic environs, but the deeper we go, the more its unique parts rust over and get replaced by 3-D-printed Hollywood assembly-line knockoffs, taming Bong’s well-intended aspirations into popcorn-flick subservience.

…

Meanwhile in the customary MCC film breakdowns:

Hey, look, it’s that one actor!: Steven Yeun (Nope, Minari) is Mickey’s “friend” and fellow loan-shark target who likewise gets hired for the journey, but lands a better position and causes more problems than he solves. Cameron Britton (the MVP of Fincher’s Mindhunter) is one of the expedition’s lead scientists. Daniel Henshall (Okja, The Babadook) is Ruffalo’s equally smarmy assistant who amplifies the Marshalls’ stereotypical religious buffoonery, which has its real-life counterparts (I wish it didn’t, but welcome to 2025) but is decades past being a cutting-edge critique.

Second-string good guys include Steve Park (Snowpiercer, In Living Color) and Angus Imrie (the voice of Star Trek: Prodigy‘s Zero). Other toadies include Tim Key from the upcoming The Ballad of Wallis Island, whose trailer got considerable art-house play during this past Oscar season.

How about those end credits? No, there’s no scene after the Mickey 17 end credits, though if you stick around that long, the final song is a reprise of Mark Ruffalo’s musical number (yes, Ruffalo “sings”) — an “original” faux-hymn called “Righteous is the Lord”. And the Special Thanks section includes a shout-out to filmmaker Edgar Wright.

Discover more from Midlife Crisis Crossover!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.